Ideas for Meshed and Resilient Implant Communications

The supporting repo in all its Claude-assisted glory for this post is here: https://github.com/BaffledJimmy/NebulaPOC.

If you are strapped for time – what about a standard for mesh communications within implants, similar to BOFs / BOFPEs or async BOFs – giving us the flexibility to abstract P2P comms away from the implant itself.

Introduction

Red Teamers have been using pivot implants for years, even Meterpreter had a variety of pivot options in the 2010s (and we’ve had netcat redirection for decades). However, in the commercial or open source sector the nature of implants have always remained P2P – you have an egress implant that beacons to the internet and then N number of pivot implants within the target environment all communicate via it.

Commercial C2 frameworks such as OST, Nighthawk and Cobalt Strike all have some element of SMB or TCP implant. The issue remains however that if you lose your egress implant then you need to regain access and then relink to the pivot implant. All being well (!!!) the chain or collection of implants will then automatically reconnect. Nighthawk also has a feature where the implant will try to failover to egress / P2P (or vice versa) if it is not possible to egress through the primary route or proxy.

Various leaks and IR reports across the years have indicated that sophisticated implants have an awareness of other implants within the operation and form their own resilient sub-network, both internally to a network but also across a network of compromised hosts on the internet. Should the communications path out of the environment be disrupted, the implants are able to use their built in routing tables to determine another route to the Internet and back to the C2 server. This could be via a different proxy, different gateway / firewall, or even a different workstation that was previously laterally moved to.

Recent improvements in VPN technology has seen products such as CloudFlare Tunnels, TailScale and Nebula (originally from Slack, now there appears to be a commercial offering from Defined Networking) come to the fore. Several people have given talks on using these for initial access, as well as for giving them a solid network connection into the environment and avoiding certain aspects of EDR inspection.

I thought it would be interesting to see if we could replicate the mesh network aspect of clever implants using some easily available technologies, as well as a few differing design considerations. In effect we are providing a network path for implant communications that is separate to the main OS operating stack, conceptually the implant has its own network stack that can (if required) auto discover new peers. The idea would be to either allow for the remote updating of the routing table inside the implants as new implants or egress routes become available, or to separate the two entirely so that the networking between implants simply becomes a mechanism down which additional capabilities can be tunneled (a glorified SOCKS proxy mesh perhaps!).

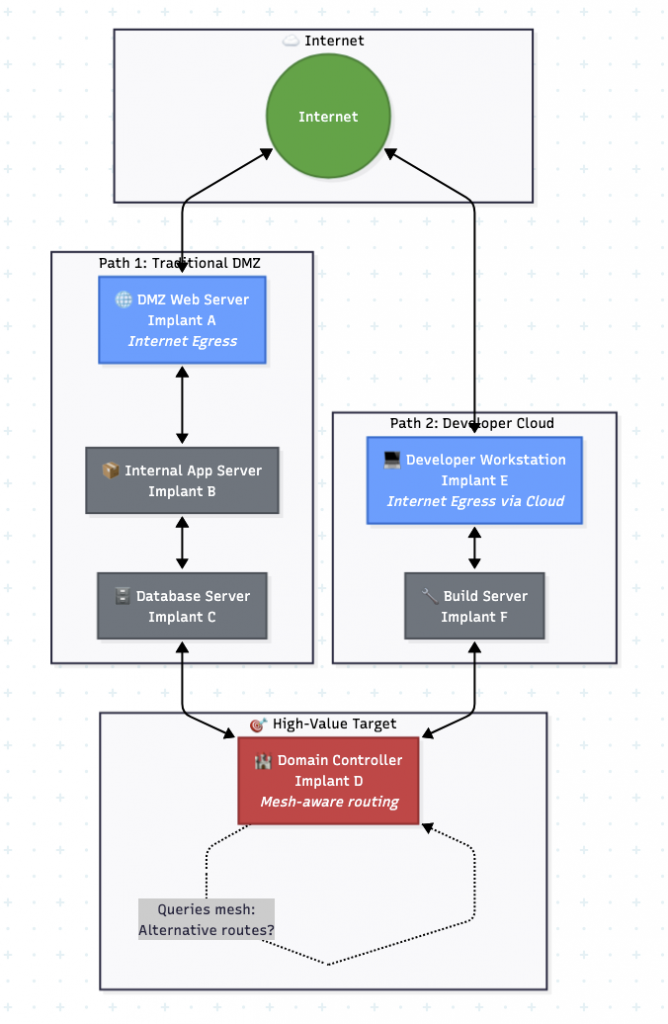

Consider how the earlier scenario would differ with a mesh-aware architecture:

In a mesh-aware model, Implant D on the domain controller knows that it can reach the internet through Implant A (via B and C) or through Implant E (via F, if reachable). If A becomes unavailable, D can query its routing table, determine that E offers an alternative path, and establish connectivity through that route.

This requires Implant D to know about Implant E’s existence and capabilities—information it could not possess in a traditional point-to-point architecture. The mesh must have shared state about which nodes can reach which networks.

Sliver can establish WireGuard interfaces without elevated privileges on many operating systems. WireGuard’s userspace implementations (wireguard-go) can create TUN interfaces using standard user permissions on platforms that support unprivileged user namespaces. This means a low-privilege implant can route traffic through the tunnel without requiring administrator or root access.

However, Sliver’s WireGuard implementation still operates on a point-to-point basis. Each tunnel connects one implant to the Sliver server or to another implant. There is no mesh discovery. If an implant’s tunnel endpoint becomes unavailable, it does not automatically seek alternative paths through other compromised hosts.

Known Implementations

Everything here is derived from open source knowledge or intelligence.

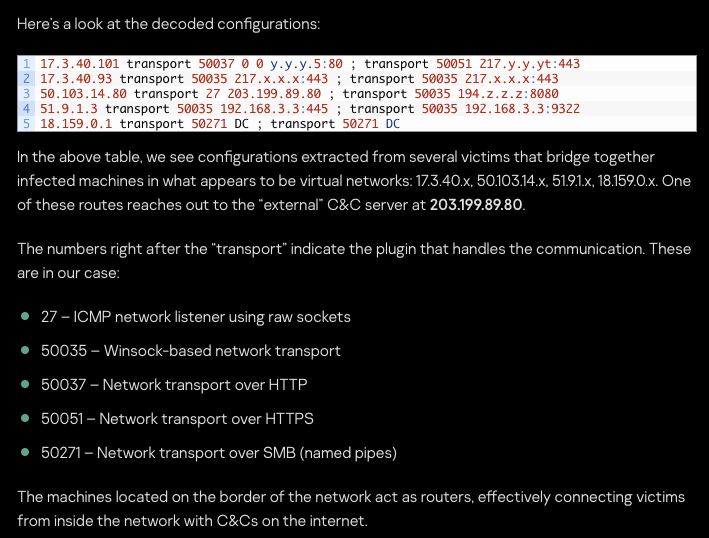

The FSB Snake malware network is reported to have forward commands, allowing for the global P2P network to simply forward operator commands until the eventual target implant is reached. The public CISA advisory that tears the implant apart is 10/10 and includes mention of the peer addressing methodology used which allows operators to manually customise the mesh network when needed. It also has a kernel module to intercept TCP sessions – something which isn’t covered in this article but that a professional implant should be able to achieve. In the lab, we just listen on a free port instead!

The Cobra implant (that can use Snake for comms) and the Regin implant (disclosed by Kaspersky) also makes specific mention of implants forming together into a mesh network, also using GSM base stations in the case of Regin. The below image includes the most relevant part of the article which can be found in References at the end.

There are also instances of China using them, as seem in APT41, APT10 and FlushDaemon. Pangu Lab also made reference to mesh networks within their breakdown of the alleged NSA Bvp47 implant.

Clearly, agencies have much longer operational horizons, much greater zero-day, big budgets and much greater capabilities as well as global scale / law exemptions – but we can use a watered down version to make our small red team a little more resilient to containment and cross-platform.

Part 1 – Controlling Server Hosted On Internet

I’m highlighting principals for designing future tools, rather than suggesting anyone starts running ./my_nebula_implant across client environments. But this series does have some differing viewpoints on how and where we should place host registration and the level of fixed immovable config or implant security that is need.

Nebula

Lighthouse

Nebula has some good documentation and some wider reading here and here. The most important component (apart from the CA) is the Lighthouse which has knowledge of all hosts – a way of getting a connection to Lighthouse is required at host registration and to know about hosts that can relay.

My understanding is that within this way of deploying Nebula there is no way of avoiding this without hardcoding hosts and IPs into each config (and the required certificates). One of the cool features of Nebula is autodiscovery of newly connected hosts, or you can use a static_host_mapping which hardcodes every host and IP in every config – labourious but also exposing a lot more information than we may need to.

Slack’s Nebula is an open-source overlay networking tool that creates encrypted mesh networks across arbitrary underlying infrastructure. I am not proposing Nebula itself as an implant (although it would work…). I’m using Nebula to demonstrate mesh networking concepts that could inform implant architecture design.

Why Nebula Though?

- Certs – Every node in a Nebula network has a cryptographic identity issued by a certificate authority. Nodes can verify peer identities and restrict communications based on certificate properties.

- Autodiscovery – Nodes can discover each other through lighthouse servers that maintain a registry of node locations. This provides peer discovery without requiring static configuration of every peer.

- Relay – Nodes that cannot communicate directly (due to NAT or firewalling) can route traffic through relay nodes that have broader connectivity.

- Doesn’t need root – Nebula can operate with or without TUN interfaces. A lighthouse or relay node can function without root privileges if it does not need to route IP traffic locally.

Relays

Relays can be a way for hosts that are in differing subnets to bridge back to the main Nebula mesh network. Conceptually, this can be a machine with two NICs, and provides a way for operators to use the Nebula network to reach into isolated environments, via the relay machine.

Lab Environment

For this POC we have various EC2 instances. These can all be deployed using the scripts in the supporting repo, which sets appropriate AWS SGs to demonstrate the various features of Nebula.

VMs

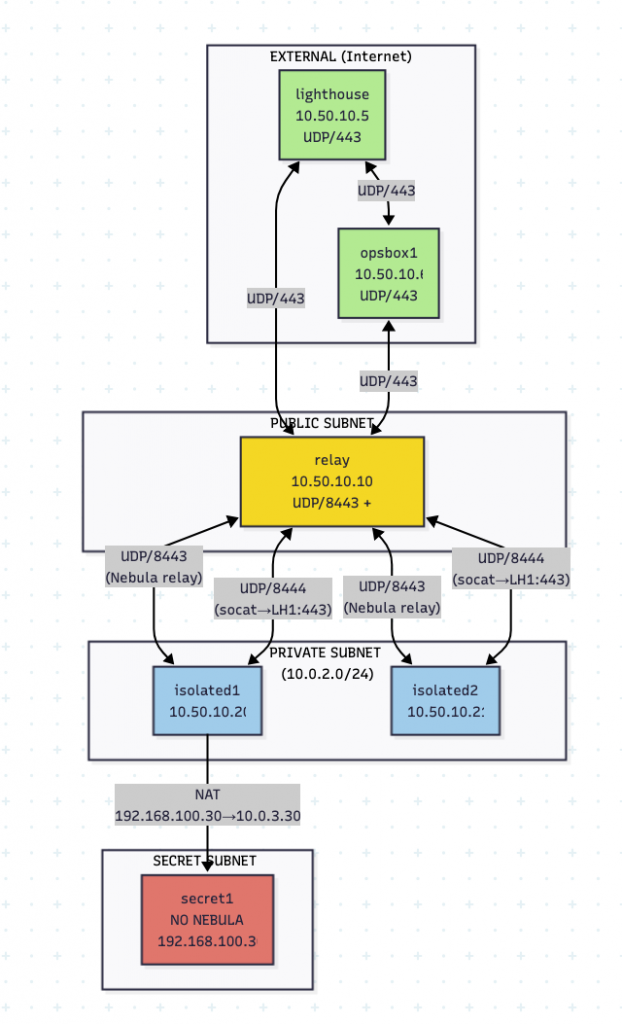

lighthouse1– Does what it says on the tin. Always good practice to have two for HA, but you could easily get away with a single one as a POC.opsbox1– A simple Ubuntu server that acts as the attacker machine from which you would deliver other post-exploitation plugins, or act as an ingress into the Nebula network.relayvm– This acts as a Nebula Relay, and represents a compromised device on the network perimeter – it bridges the gap between the public internet and the target environment.isolated1andisolated2– these VMs do not have internet access and cannot be reached directly. They also cannot communicate with each other.secret1– this host is not managed by Nebula (in this scenario, it has not been directly compromised), but hosts our$target_webappin the form of the nginx default page. This VM cannot be reached from anywhere other thanisolated1.

Through the wonders of Uncle Claude and supplying our source Terraform, we are able to visualise the infrastructure as shown below.

Design Considerations for Network Resilient Implants

Execution Guardrails

Shellcode and loaders will already be keyed to a variety of environment-specific variables, and the encryption key may be stored externally. This point refers to ensuring that the network is only able to establish communications within certain CIDR ranges. This would help defeat any analysis that took place in a sandbox environment as it is extremely unlikely to match at the network layer, or should the user migrate their laptop (or similar) into an environment that is out of scope. It would be excellent if new permitted subnets could be distributed to all (or a subset) of implants as the red team gain additional access, automatically or manually.

Proxy List

Organisations often used to restrict egress over VPN protocols and enforce all traffic through a L7 firewall or other similar appliance. This is much less common since COVID, especially with the prevalence of TLS VPN technologies. However, web traffic is still likely to egress through an appliance, or through a service such as ZScaler or similar. It is important that the network traffic, port and protocol is as close to ‘real life’ as possible, allowing traffic to egress on common ports or similar. The chance of this being permitted is much greater since organisations enforced return to office, but then still made use of their BYOD / Cloud infrastructure that they had built during COVID. Whichever implant is acting as the final egress point (for N numbers of internal pivot implants), it should be capable of attempting a variety of C2 addresses, protocols but also a list of hardcoded proxy addresses. It would be even better if this list of options for final egress was able to be remotely updated in a manner similar to a lot of the Nighthawk implant configuration without requiring new shellcode generation.

Next Hop

It may upon first examination be faster and simpler to have each implant have a full list of all implants within the operation which is dynamically updated (or some form of broker such as Lighthouse that maintains awareness of everything). However during reverse engineering or some other sandboxing process, this could result in a list of all implants within the environment being obtained by the defenders, which would get you contained and eradicated quite quickly. Encryption and other malware writing techniques can help, however eventually it is likely that the functionality would be revealed.

One alternative option is that each implant only has knowledge of the next hop needed to egress in the environment, rather than a full list. This introduces it’s own complexity around verifying that the next hop is still active and still functioning, with a backup option if it is found to be unavailable or unroutable.

Route Priority

The operators should be able to configure and change the route that the implant is beaconing from depending on the use case (once a week checkins vs SOCKS proxy). This could include changing routes depending on latency, country of origin, stability, capacity or ‘blends in’. Factors such as time of day affecting the frequency of communication and jitter are also things that need to be designed in and configurable on the fly.

To be able to present this information to the operator so they can make a decision, also creates an implicit dependency to collect and analyse a large amount of non-implant related telemetry.

Credential Material / Authentication

Nebula makes use of certificates on a per host basis which is the authentication to join the mesh network. Clearly the confidentiality of this material is critical. When designing the implant PKI infrastructure, the operation-specific root key should be stored offline, with issuing keys used to generate authentication for each implant or compromised host.

With Nebula, this means that to establish a new network route for implant comms, you’d need to push the implant and the certificate onto the filesystem and hide it appropriately. There is a token demonstration of this with the use of systemd-creds within the lab environments, but it certainly isn’t production ready. Whilst researching this I had never heard of systemd-creds, which appears to be loosely similar to DPAPI in terms of host based keys for encryption. Decryption of the certificates needed to join the mesh or sign C2 messages should only be possible in the right context – hostname, user context or time bound.

It is also essential to be able to cut off an implant from the mesh network should it be out of scope, or be being debugged by defenders. This can be combined with additional implant design decisions like not running if certain processes (windbg, wireshark, ghidra etc) are seen running on the host, or if the host looks like an underpowered VM (a sandbox).

A way of killing an implant that is unresponsive would be to configure it to exit cleanly if it has no network connections for X time period. By cutting it off from the mesh, it would then have no network connection and then exit cleanly as requested. Consideration should be given to the correct time period for this though, especially when considering that servers go offline for maintenance, users close laptops for holidays etc.

Nebula can revoke a machine’s certificate, which is then distributed to all other nodes and then the ‘lost’ node is prevented from rejoining. In our POC environment, a defender who was able to recover and understand the Nebula certificate would be able to see the addressing scheme, which network segments were accessible, times and a fingerprint for network traffic.

Privilege Level

Not every implant will be running as a root backdoor. Nebula has some flexibility in that it can function within a low privilege level (tun.disabled: true), however some functionality is not available. This can be seen in Lab 2 where the DMZ Lighthouse is low-privilege. Hosts without the tun interface can act as relays or Lighthouses, but cannot send traffic within the mesh.

Mesh networks should be able to function as relays / next hops and ‘routing table distribution points’ across multi platform implants, regardless of privilege level. A simple use case would be a low privilege implant on a jump server may need to act as an egress route (back to another low privilege user shell on an endpoint) for a SYSTEM implant on a segregated Tier 0 server.

Lower privileged mesh implants could have lesser functionality, although the ability to act as a relay is essential – without elevated privileges, this would happen at the application-layer rather than pure network layer.

Hiding Network Connections

All of the POC concepts in this lab make use of the normal network stack and creating a new interface (where applicable). However in reality we would want to hide new interfaces and active connections from netstat and other tooling. Achieving this is definitely outside the scope of this article, but by the time you are implementing your own network stack in a mesh of implants, you can probably figure it out!

Staging

If we wish to implant a target server rather than simply having network access to it, there will be a need to stage implant shellcode on a pivot implant that is retrieved via the Stage 0 or loader that is run on the new target server. This is because the implant may not at that point have full knowledge of the wider mesh (this would be pushed to the implant at first checkin to prevent hardcoding all of the information in and exposing it to analysis at execution-time). A small stub would be needed to host it on the pivot server in a manner similar to LiquidSnake (shellcode retrieves full implant from a named pipe) or other tools. RastaMouse touches on this topic lightly in the original CRTO syllabus for example, with rportfwds on compromised egress beacons allowing for isolated beacons to retrieve staged shellcode as they reach back to egresshost.domain.local:8080.

Timestamping & Route Information

Most C2s (although there are several commercial C2s which don’t…) will record the timestamp an operator sent the command from their UI, the time it was received by the C2 server, the time the implant received it, and the time that the task was completed and the response sent back. This relies on the universal assumption that network comms and internet will ‘just work’; no network based timing telemetry is collected whatsoever.

With a mesh network, there is another layer of network telemetry that we need to be aware of, especially when we have multiple routes out of an enclave and we need to know which routes are go and which routes are no-go. This can also be relevant for network communications that have endpoints that cross between internet-connected / corporate networks and airgapped / IOT networks.

It is important to collate up/downs of the mesh network as a whole, checkin times for the nodes (on Lighthouse in our Nebula example), timestamps that commands for airgapped machines were placed in the queue, and what time they were distributed to the airgapped network, for example when the sysadmin moves his laptop between environments. Further, we need to collect (in a machine readable format) which network path the traffic took, as well as the routes it could have taken. This allows us to identify fallback routes ahead of time that other implants may need configuring for (or auto-failover) if the primary route fails.

Lets dig into a few use cases so we can see different deployment options for network resilient implants, as well as any tradeoffs that exist.

The use cases are

- Lab 1 – Externally Hosted Lighthouse – control server hosted on attacker infrastructure in

$cloud_provider. - Lab 2 – Lighthouse hosted on the DMZ, simulating a compromised webserver or VPN appliance.

- Lab 3 – demonstrating how a simple store and push mechanism can work to queue tasks, allow hosts to leave the mesh as it is connected to an airgapped network, carry out the task (or more likely in this scenario, retrieve C2 output from another implant) then rejoin the mesh and distribute the output.

Each lab has some definitely-not-Claude Terraform, Ansible, and a test script to show that Nebula is doing the routing with some tests that expect to fail and some that are expected to pass.

Lab 1 – Externally hosted Lighthouse

In this lab, the Lighthouse (the control server) is hosted on attacker infrastructure, where the privilege level is root. An opsbox acts as the attacker VM and can make use of Nebula to access the other nodes. In this construct the Lighthouse has no TUN interface and so cannot participate in the traffic, it simply acts as a broker. As this machine contains the root certificate in our example, it being unavailable to the hostile target infrastructure is a good thing. This keeps all ‘critical material’ in the hands of the attacker, although it has downsides that can be seen later in this section, especially relating to traffic relaying from relayVM.

However, this setup makes use of static_host_map, so there is no dynamic host discovery. This model makes it cumbersome to add new hosts upon implant deployment as it needs updating across the fleet. The engineering effort to do this in a secure fashion is likely to be significant, as well as leading to lots of ‘why can’t I reach a particular target’. The aim of the mesh topology is to make

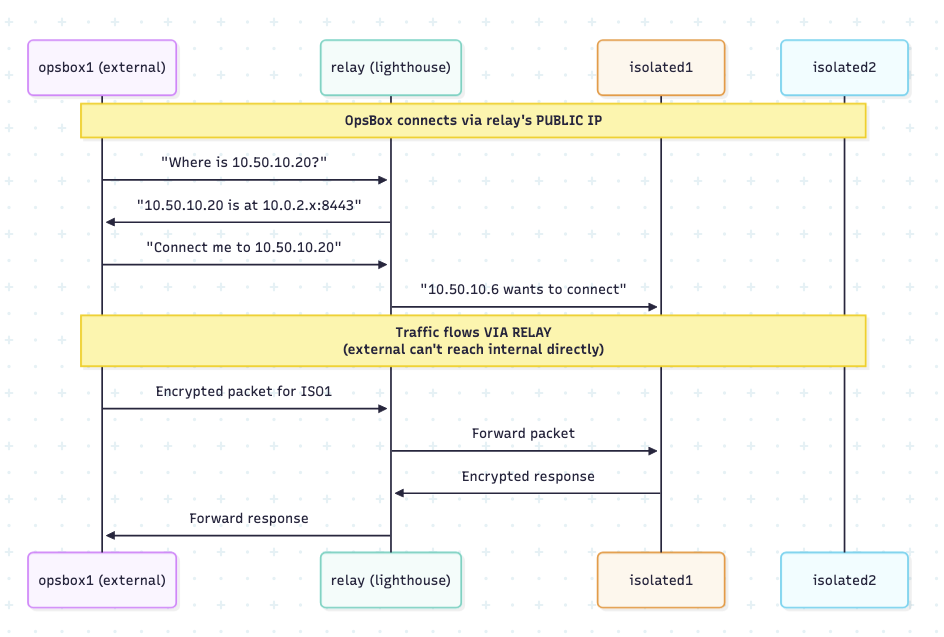

Note: In the below diagram, TCP/22 is allowed inbound to all subnets simply to allow Ansible to run easily and for troubleshooting, removing the complexity and headache of SSH -J etc.

- lighthouse1: 10.50.10.5

- opsbox1: 10.50.10.6

- relay: 10.50.10.10

- isolated1: 10.50.10.20

- isolated2: 10.50.10.21

- secret1: 192.168.100.30 (via unsafe_routes through isolated1)

The only issue with this setup (more of a Nebula restriction) is that the relayVM (which acts as the pivot point to isolated1 and isolated2, requires a socat pipe to tunnel UDP Nebula traffic back to the external Lighthouse due to them being in a private, non-routable subnet and not being able to bind to low ports. The relayVM does not run as root, representing a compromised machine where you have user-land access (such as a laptop or jump server) but not SYSTEM or root.

EDIT: The socat requirement looks like it might be possible to remove if all of the certificates are pre-positioned on all hosts – this would allow your newly compromised hosts to communicate within the mesh, WITHOUT having to establish direct handshake communications with the Lighthouse first. This makes it much more ‘realistic’ for our POC and scenarios.

This could be possible because the Lighthouse provides the following functionality

- Dynamic Peer Discovery

- Physical Address Resolution

- NAT Hole Punching

However, if the certificates are all pre-positioned on all hosts, they already contain Nebula IPs, group memberships and ACLs, routable subnets and the CA chain. Relays will learn about peer addresses when the peer connects. I confirmed this in the lab, however relaying functions don’t work – so if you don’t want any external Lighthouse functionality, you can hardcode all addresses in a static_host_map and provided the hosts can reach each other, it will work.

Back to Lab 1….

Looking through the Terraform for Lab 1, we can see that there are AWS SGs that enforce the segregation between the isolated1 VM and the relayVM.

# Secret1 security group - only accepts HTTP from isolated1's ENI

resource "aws_security_group" "secret" {

name = "${local.name_prefix}-sg-secret"

description = "Secret1 - HTTP only from isolated1 ENI"

vpc_id = aws_vpc.main.id

# HTTP from isolated1's secret-subnet ENI only

ingress {

description = "HTTP from isolated1 ENI"

from_port = 80

to_port = 80

protocol = "tcp"

cidr_blocks = ["10.0.3.10/32"] # isolated1's ENI IP

}If you check the Ansible that deploys and configures all the VMs, you can see that secret1 does not have Nebula installed and thus is not part of the mesh. It is actually on a 192.168.x.x IP address. You are able to use Nebula with the unsafe_routes argument to allow machines to egress from Nebula into unmanaged or uncompromised subnets.

In this case, we can see that opsbox1 is able to ping both isolated1 and isolated2, as well as reaching secret1 on TCP/80, because the traffic egresses the mesh from isolated1 and reaches the target webserver on secret1.

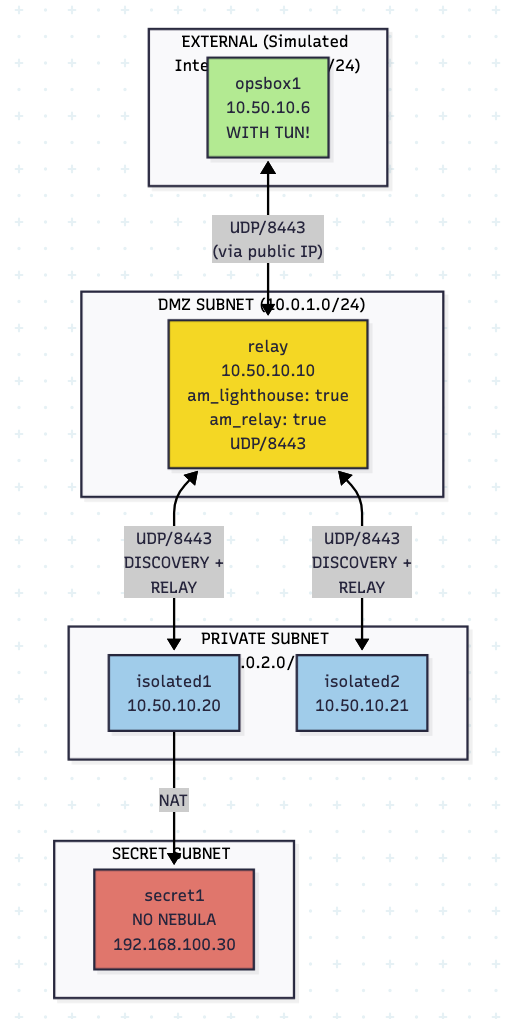

Lab 2 – Lighthouse on Target DMZ

This deployment model pushes the Lighthouse functionality to a compromised machine into the target infrastructure, with all of the credential material downsides this brings. Encryption and obfuscation of secrets at rest becomes even more critical. For this deployment model to work, a more advanced mesh or implant topology is needed to hide this authentication material. However, it does reduce the amount of heartbeat traffic that needs to egress the environment and could be suited for longer engagements.

The main advantage (although not tied directly to the physical location of the Lighthouse, simply to show the two options – static_host_map vs autodiscovery) is that we don’t need to manage which hosts can join the mesh in advance. Imagine the headache if you needed to generate and push out configs to every single implant across a large implant network if this was required. With this model, you still need to generate certificates and distribute it to the newly compromised host, but this is 5% of the work compared to managing the config manually.

The traffic flow looks like this, with the relayVM acting as a Lighthouse and a relay at the same time (hence no socat required).

Lab 3 – Air Gap Laptop

This scenario represents a user who is moving their laptop between an offline environment and a corporate environment after being unknowingly compromised.

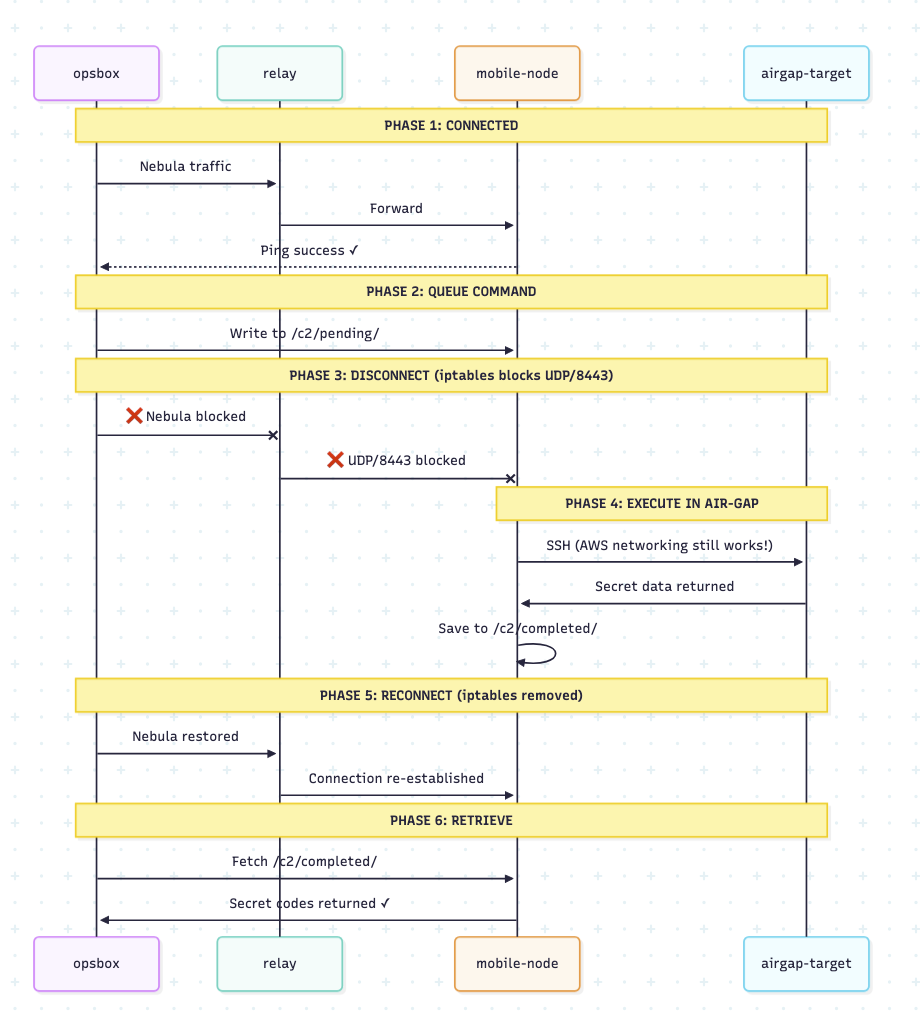

The idea is to demonstrate the importance of the egress implant being able to deliver commands to the compromised machine which is then deployed against other targets in the offline or IOT environment. This could involve staging some exploitation kits, shellcode or simply a port scanning module. The implant on the compromised laptop does the port scanning when connected to the offline subnet, caches the response and then when the target has normal connectivity again, his laptop rejoins the resilient mesh and returns the output back to the operator.

In this instance, there is an iptables rule in the lab that kills the main connection back to the mesh and allows the laptop to push ‘C2’ (simulated via SSHing to the airgapped machine and retrieving a simple file) to the offline machine, then it reestablishes mesh connectivity after the iptables rules are dropped.

The flow looks like this:

This sort of connectivity model is pretty essential for any implant mesh that will deal with intermittent or sporadic network connectivity. A complexity that is introduced is that the corporate and airgapped network are likely using very different IP addressing subnets, making it key that the implant uses its own scheme for next hop knowledge and is unaffected by the changes from 10.x.x.x to 192.168.x.x on the compromised laptop side.

It is possible to see the mechanism in Lab 3 output:

- CONNECTED: Verify opsbox can ping mobile-node via Nebula

- QUEUE: Write command to

/c2/pending/mission-001.cmd - DISCONNECT (simulate moving to another subnet):

iptables -A OUTPUT -p udp --dport 8443 -j DROP - EXECUTE: Mobile-node SSHs to airgap-target, runs

/secret/gather-intel.sh, saves to/c2/results/(simulate receiving tasking output from implant) - RECONNECT: Remove iptables rules (reconnected to corporate LAN, restart Nebula

- RETRIEVE: Opsbox fetches results containing secret codes (Alpha, Bravo, Charlie)

Conclusions

As certain red teams move to a longer term, almost ‘managed service’ style of red teaming or continuous assurance, the idea of resilent and mesh networks becomes more appealing. Whilst the commercial sector will not be compromising third party servers to act as proxies or redirectors (hopefully), a lot of the concepts discussed here are relevant to in-network persistence.

It also opens up whole new detection surfaces for defenders, as detecting internal RPC (top tier implants may not use SMB for comms) or VPN (Nebula) traffic internally can be much more difficult until tooling catches up.

Perhaps we could come up with a standard way of doing meshed resilient implant communications, with a sort of industry standard whilst still allowing for flexibility and customisation – similar to BOFs / BOFPEs or ASync BOFs being able to be used in a variety of implants.

References

- Main Sources

- CISA Advisory AA23-129A – “Hunting Russian Intelligence ‘Snake’ Malware” (May 2023) — https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/cybersecurity-advisories/aa23-129a

- Slack Nebula Documentation – https://nebula.defined.net/docs/

- Nebula GitHub Repository – https://github.com/slackhq/nebula

- systemd Credentials Documentation – https://systemd.io/CREDENTIALS/

- Russian Operations

- G-Data – “Uroburos: Highly complex espionage software with Russian roots” (February 2014)

- BAE Systems – “The Snake Campaign” (2014)

- Kaspersky GReAT – “The Epic Turla Operation” (August 2014) — https://securelist.com/the-epic-turla-operation/65545/

- CIRCL.LU – “TR-25 Analysis – Turla / Pfinet / Snake / Uroburos”

- Western Attribution

- Kaspersky GReAT – “Regin: nation-state ownage of GSM networks” (November 2014) — https://securelist.com/regin-nation-state-ownage-of-gsm-networks/67741/

- Pangu Lab – “Bvp47: A Top-tier Backdoor of US NSA Equation Group” (February 2022)

- Microsoft Security Blog – “Analyzing Solorigate: The compromised DLL file that started a sophisticated cyberattack” (December 2020)

- Mandiant – “Highly Evasive Attacker Leverages SolarWinds Supply Chain to Compromise Multiple Global Victims” (December 2020)

- Chinese Operations

- FireEye/Mandiant – “APT41: A Dual Espionage and Cyber Crime Operation” (August 2019)

- PwC/BAE Systems – “Operation Cloud Hopper” (April 2017)

- ESET WeLiveSecurity – “PlushDaemon compromises network devices for adversary-in-the-middle attacks” (November 2025)

- IoT/Router Targeting

- Cisco Talos – “VPNFilter: New Router Malware with Destructive Capabilities” (May 2018) — https://blog.talosintelligence.com/vpnfilter/

- Red Team Tooling References

- Nettitude Labs (Doug McLeod): “Operational Security with PoshC2 Framework” — Domain keying and sec.log analysis